Junior Tennis Has a Cheating Problem—and a Fix

There is a dirty little secret in the cloistered world of competitive junior tennis—cheating and gamesmanship are rampant.

For many children and parents, their first exposure to the junior tennis circuit is a shock because junior tennis is one of the few sanctioned sports that requires kids to referee their own matches and keep their own score.

Many parents report a traumatizing first tournament experience for their child, full of tears and frustration. It is a well-known fact within the tennis community that many kids play only one competitive tournament and never return to the circuit.

Interestingly, the United States has far more high school tennis players than juniors who compete regularly in sanctioned weekend tournaments. The National Federation of State High School Associations reported that 353,601 students participated in U.S. high school tennis during the 2023–24 school year (NFHS, 2024). That scale helps explain why many “nice kids” choose high school tennis, where the environment is less cutthroat and cheating and gamesmanship are minimized.

On a Saturday or Sunday morning, you will not find kids on a soccer field keeping their own score or players on a basketball court calling their own fouls. Yet in tennis, children as young as eight years old do precisely that. Parents sit or pace helplessly on the sidelines and are not allowed to intervene when disputes arise.

It is true that most sanctioned tournaments employ roving umpires or allow players to request an official to assist with disputes. But by the time an umpire arrives, it is often too late. Savvy players know how to manipulate both the system and the referee, or they simply resume questionable behavior once the umpire leaves.

The case for automated line calling is not just practical or emotional; it is scientific. Human perception has clear limits, especially when objects move at high speed. In tennis, the ball routinely travels at speeds of 70 to 100 miles per hour, changes direction abruptly, and often lands within millimeters of a line. Under these conditions, even trained observers rely heavily on prediction rather than direct visual confirmation. Vision science shows that the human visual system cannot continuously track fast-moving objects with high spatial precision; instead, the brain relies on brief fixations and predictive extrapolation, which becomes increasingly unreliable as object speed increases (Spering, Pomplun, & Carrasco, 2011). As decision time shrinks and spatial margins narrow, perceptual uncertainty rises sharply, meaning sincere observers can confidently make incorrect calls even without any intent to cheat (Land & McLeod, 2000).

Disagreement does not require dishonesty. The visual system is often simply asked to do something it cannot reliably do. Because this predictive process begins at ball speeds well below those seen in competitive tennis—often as low as 40–50 miles per hour at typical court distances—people routinely overestimate how much they are actually seeing. By the time ball speeds reach 70–100 miles per hour, perception has shifted almost entirely from continuous visual tracking to prediction. The brain constructs a best-guess model of the ball’s path from early trajectory cues and prior experience, and that model feels vivid and certain even when it is inaccurate. Near a line, where decisions hinge on a few millimeters and milliseconds, small predictive errors can easily reverse an “in” or “out” call. Disagreements in these moments are therefore not always signs of dishonesty so much as signs that the visual system has been pushed beyond its biological limits. When emotional stakes are added—as they inevitably are in competition—confidence in incorrect judgments often increases rather than decreases.

These perceptual limits are magnified in junior tennis because children’s visual and neurological systems are still developing. Visual acuity alone is not the issue; the challenge lies in how the brain integrates vision, motion, timing, and spatial judgment under pressure. Children and adolescents have less mature visual-motor coordination, slower neural processing speed, and less stable predictive tracking than adults (Sinno et al., 2020). The systems responsible for anticipating where a fast-moving object will land—rather than reacting to its current position—continue to develop well into adolescence.

In practical terms, young players are being asked to make split-second spatial judgments that challenge their developmental capabilities. Tracking a tennis ball requires continuous prediction, error correction, and rapid updating of visual information. In children, these processes are noisier and less reliable. Children can make these judgments, but with less accuracy and more variability. Even when a child is looking directly at the ball, the brain may misjudge its speed, trajectory, or landing position, especially when the ball changes direction or lands near a line.

Experience does not fully compensate for these constraints. While repetition improves anticipation, it cannot override developmental limits. Asking an eight- or ten-year-old to make precise line calls at competitive speeds is not a test of character—it is a mismatch between task demands and neural readiness. Even when a child wants to be fair, their nervous system may not yet be capable of producing consistently accurate judgments.

The problem is compounded by emotional and cognitive load. Competition activates stress responses that narrow attention and degrade fine perceptual discrimination, effects that are stronger in children than in adults. Add the pressure of winning, rankings, parental expectations, or fear of confrontation, and perceptual accuracy declines further. Under these conditions, children may appear dishonest when, in fact, they are overwhelmed.

This creates a damaging feedback loop. Children who are developmentally less able to officiate accurately may be accused of cheating, while those who are more aggressive or confident may dominate disputes regardless of correctness. Over time, this dynamic rewards assertiveness over accuracy and teaches young players that outcomes depend as much on social leverage as on skill. For quieter or more conscientious children, the experience can be discouraging enough to drive them away from competitive tennis entirely.

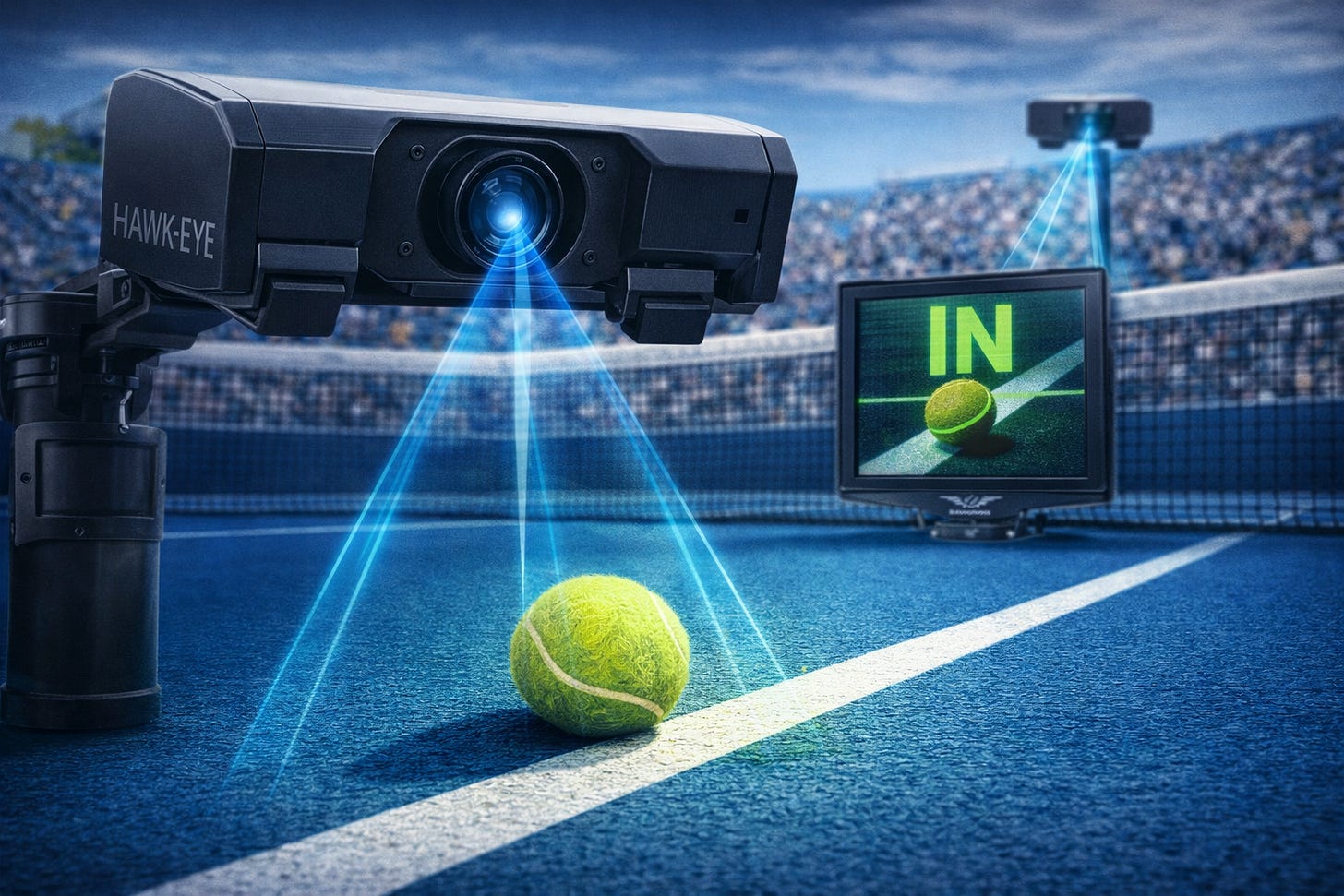

Automated line-calling systems remove this burden. Multi-camera tracking technologies objectively measure the ball’s position across space and time, unaffected by factors such as fatigue, stress, intimidation, or bias. Electronic line-calling systems use multiple high-speed cameras to reconstruct ball trajectory in three dimensions, providing objective and repeatable decisions (Pluim et al., 2014). Just as importantly, they remove the social, emotional, and cognitive pressure on young players to act simultaneously as competitor and official.

The downstream effects are substantial. When disputes disappear, attention shifts back to playing, learning, and enjoyment. Kids play more freely. Coaches coach instead of mediating conflict. Parents relax instead of bracing for confrontation. The competitive environment becomes developmental rather than adversarial.

From a youth development perspective, this shift matters deeply. When children repeatedly experience competition as unfair or hostile, they internalize the message that success requires bending rules or enduring injustice. When competition feels transparent and fair, they learn that effort and skill matter. Technology, in this case, does not undermine character—it protects it.

There is also an equity dimension. Self-officiated systems tend to advantage the most aggressive, experienced, or socially dominant players, not necessarily the most skilled. Automated line calling levels the playing field and protects quieter kids, newer competitors, and families unfamiliar with the unwritten norms of junior tennis. Fairness should not depend on personality or tolerance for intimidation.

Taken together, the science of perception, the psychology of competition, and the realities of child development all point in the same direction. Asking children to self-officiate high-speed competitive matches is not a test of integrity or toughness; it is a structural mismatch. Automated line calling does not weaken the game of tennis. It corrects a long-standing flaw in how the sport asks children to compete.

The big question is why. Why have leaders of the sport—across the ITF, USTA, UTR, and other sanctioning bodies—failed to put an end to cheating in junior tournaments?

Some argue that it would be too costly to provide proper supervision. Others insist that self-officiating builds mental toughness and independence. “It’s just part of the game,” they say. Others shift responsibility entirely to parents and coaches, framing cheating as a societal issue rather than a tennis problem. There is also a group of deniers who claim cheating is not prevalent enough to warrant concern.

Meanwhile, many coaches working directly with junior players have grown alarmed by the extent and intensity of the problem and have advocated for change. Their concerns, however, have been largely brushed aside for decades. Institutional inertia, reinforced by rationalization and excuse-making, has been a powerful force.

It is time to stop cheating in junior tennis. It is time to stop pretending this is normal or acceptable. All stakeholders share a common goal: increasing the number of kids who love the sport. Very few families want to invest time, money, and emotion in a competitive environment where cheating is built into the system.

Junior tennis should be designed and offered as a product that families are eager to choose. Tournament organizers and governing bodies should coordinate to provide events with a clear commitment to fair play, a guarantee against cheating, and accurate line calling. The sport and the kids deserve nothing less.

For the first time in a long while, there is genuine reason for optimism. Advances in technology are finally offering a practical solution to a problem that once seemed unsolvable. Automated line-calling and video review systems—powered by cameras, artificial intelligence, and computer vision—are beginning to transition from professional tours into clubs and junior competitions.

I have had students experience automated line-calling review for the first time, and the feedback has been consistently positive. Arguments disappear. Emotional tension drops. Kids stop policing one another and start focusing on playing tennis. Parents relax. Matches move faster. The experience feels calmer, fairer, and more professional. Perhaps most importantly, children walk off the court believing that outcomes were determined by skill and effort, not manipulation.

As the cost of this technology continues to fall, widespread adoption becomes increasingly likely. Automated line calling has the potential to fundamentally reshape the junior tennis landscape. Imagine tournaments where cheating is no longer part of the rite of passage because it is no longer possible. Imagine kids learning resilience, sportsmanship, and confidence in an environment that feels fair and equitable.

This is an exciting moment for the sport of tennis. Artificial intelligence and camera technology are no longer threats to tradition; they are tools that can restore fairness, integrity, and joy to the sport. If tennis chooses to embrace them, the next generation of players may grow up in a competitive environment where cheating is no longer expected—and where every child has a fair chance to love the game.

What You Can Do Now

Parents, coaches, and players who care about the future of junior tennis can help accelerate this change. One concrete step is to contact local and national representatives at the USTA and UTR and ask them to prioritize automated line-calling and review technology at junior tournaments, especially in self-officiated formats. Governing bodies respond to sustained, collective pressure—and fair play is a goal nearly everyone agrees on.

Families can also vote with their time and money. When possible, register for tournaments held at clubs that use automated line calling or video review, and let tournament directors know that this technology influenced your decision. Clubs and organizers pay close attention to participation patterns, and demand is often the strongest catalyst for adoption.

References

National Federation of State High School Associations. (2024). High school athletics participation survey: 2023–24 school year. https://assets.nfhs.org/umbraco/media/7213111/2023-24-nfhs-participation-survey-full.pdf

Spering, M., Pomplun, M., & Carrasco, M. (2011). Tracking without perceiving: A dissociation between eye movements and motion perception. Psychological Science, 22(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610395399

Sinno, S., Najem, F., Abouchacra, K. S., Perrin, P., & Dumas, G. (2020). Normative values of saccades and smooth pursuit in children aged 5 to 17 years. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 31(6), 384-392. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.19049

Land, M. F., & McLeod, P. (2000). From eye movements to actions: How batsmen hit the ball. Nature Neuroscience, 3(12), 1340–1345. https://doi.org/10.1038/81887

Pluim, B. M., Crespo, M., Reid, M., & Savelsbergh, G. J. P. (2014). Officiating in tennis: A review of decision-making, accuracy, and technology. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(8), 706–712. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091834

Rampant cheating was definitely one of the reasons I was so turned off by junior tennis.

Really compelling framing of the perceptual limits here. The distinction between kids being dishonest versus their visual system literally being incapable of tracking 70+ mph balls is huge, esp. when neural processing is still developing. I coached youth soccer briefly andit was night and day compared to self-officiated systems. The automated tech basically removes the false choice between character-building and fairness.